Being a Toastmaster, I am always fascinated by great speakers and great speeches. I like to learn from those men and women and improve my own speaking.

Last year, I shared a few of my thoughts about the famous “I Have A Dream” speech by Martin Luther King Jr. You might want to check that out by clicking here.

Along the way, I have come across many impactful speeches throughout history and I have always enjoyed perusing those words that ring through time. My thanks go out to my awesome friend, Distinguished Toastmaster Alan Balthrop, who loaned me a book of about 50 most famous speeches from around the world.

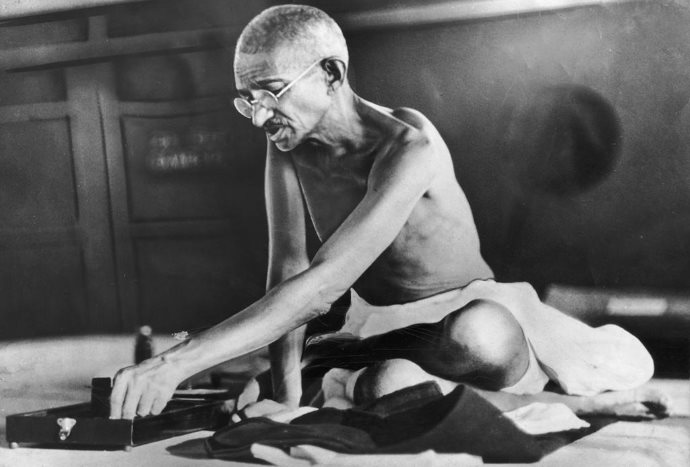

Among those 50 famous speeches, I found this great speech by Mahatma Gandhi. It was delivered in a packed courtroom to about 200+ people on March 18, 1922.

Growing up in India, I learned a lot about the struggle for Indian independence and those freedom fighters. I had never come across this speech anywhere. Now that I found it, let me share it here with my readers.

The Background – A Brief Introduction For The Trial

As soon as legislation called the “Rowlatt Act” was passed in March of 1919, it inspired immediate unrest. This act granted greater power to the police to arrest without cause those suspected of sedition.

Mahatma Gandhi was seriously ill at the time and it was believed that he might be dying. However the “Rowlatt Act” restored his vitality and inspired him to call for a nationwide general strike on April 6, 1919 to protest the government’s policy. The strike was intended to be peaceful in keeping with Mahatma Gandhi’s belief in non-violence.

Unfortunately, a few protests led to violent confrontations with British authorities. These altercations eventually created a sequence of events that led to the Jalliawalla Bagh massacre that occurred when Brigadier General Reginald Dyer opened fire on unarmed civilians. This resulted in the deaths of several hundred men, women and children and injured thousands of people.

Mahatma Gandhi traveled from city to city and village to village to rally the Indian masses. In the process, he became not only a radical political figure but also a moral leader for the masses in India. His simple manner easily won the hearts of the countrymen and so he had a large following.

The Arrest Of Mahatma Gandhi And The Trial

Mahatma Gandhi was arrested on March 10, 1922 and charged with sedition for several of the articles he wrote in the weekly newspaper he edited named Young India.

The case was brought to court at 12 Noon on March 18, 1922 in the city of Ahmadabad. He was accused of attempting to excite disaffection towards His Majesty’s Government.

When Mahatma Gandhi entered the Central Hall of the Government Circuit House that day, about two hundred spectators inside the improvised courtroom stood up as a mark of respect to the frail figure dressed only in a loincloth.

Mahatma Gandhi pleaded guilty on all charges without any hesitation.

However, when a court asked him if he would like to make a statement on the question of his sentence, Mahatma Gandhi took the opportunity to address the courthouse.

This address by Mahatma Gandhi was not an ordinary address. It was this speech that made that trial such a “momentous and historic” trial. The issue raised by Mahatma Gandhi was not one arising ostensibly out of a breach of a section of a law but the perennial one of “Law versus Conscience.” The trial was endowed with classic grandeur enveloped with the Socratic passion for truth emanating from Mahatma Gandhi’s lips.

The Actual Text Of Mahatma Gandhi’s Address To The Court

Before I read this statement I would like to state that I entirely endorse the learned Advocate-General’s remarks in connection with my humble self. I think that he has made, because it is very true and I have no desire whatsoever to conceal from this court the fact that to preach disaffection towards the existing system of Government has become almost a passion with me, and the Advocate-General is entirely in the right when he says that my preaching of disaffection did not commence with my connection with Young India but that it commenced much earlier, and in the statement that I am about to read, it will be my painful duty to admit before this court that it commenced much earlier than the period stated by the Advocate-General. It is a painful duty with me but I have to discharge that duty knowing the responsibility that rests upon my shoulders, and I wish to endorse all the blame that the learned Advocate-General has thrown on my shoulders in connection with the Bombay occurrences, Madras occurrences and the Chauri Chaura occurrences. Thinking over these things deeply and sleeping over them night after night, it is impossible for me to dissociate myself from the diabolical crimes of Chauri Chaura or the mad outrages of Bombay. He is quite right when he says, that as a man of responsibility, a man having received a fair share of education, having had a fair share of experience of this world, I should have known the consequences of every one of my acts. I know them. I knew that I was playing with fire. I ran the risk and if I was set free I would still do the same. I have felt it this morning that I would have failed in my duty, if I did not say what I said here just now.

I wanted to avoid violence. Non-violence is the first article of my faith. It is also the last article of my creed. But I had to make my choice. I had either to submit to a system which I considered had done an irreparable harm to my country, or incur the risk of the mad fury of my people bursting forth when they understood the truth from my lips. I know that my people have sometimes gone mad. I am deeply sorry for it and I am, therefore, here to submit not to a light penalty but to the highest penalty. I do not ask for mercy. I do not plead any extending act. I am here, therefore, to invite and cheerfully submit to the highest penalty that can be inflicted upon me for what in law is a deliberate crime, and what appears to me to be the highest duty of a citizen. The only course open to you, the Judge, is, as I am going to say in my statement, either to resign your post, or inflict on me the severest penalty if you believe that the system and law you are assisting to administer are good for the people. I do not except that kind of conversion. But by the time I have finished with my statement you will have a glimpse of what is raging within my breast to run this maddest risk which a sane man can run.

I owe it perhaps to the Indian public and to the public in England, to placate which this prosecution is mainly taken up, that I should explain why from a staunch loyalist and co-operator, I have become an uncompromising disaffectionist and non-co-operator. To the court too I should say why I plead guilty to the charge of promoting disaffection towards the Government established by law in India.

My public life began in 1893 in South Africa in troubled weather. My first contact with British authority in that country was not of a happy character. I discovered that as a man and an Indian, I had no rights. More correctly I discovered that I had no rights as a man because I was an Indian.

But I was not baffled. I thought that this treatment of Indians was an excrescence upon a system that was intrinsically and mainly good. I gave the Government my voluntary and hearty co-operation, criticizing it freely where I felt it was faulty but never wishing its destruction.

Consequently when the existence of the Empire was threatened in 1899 by the Boer challenge, I offered my services to it, raised a volunteer ambulance corps and served at several actions that took place for the relief of Ladysmith. Similarly in 1906, at the time of the Zulu ‘revolt’, I raised a stretcher bearer party and served till the end of the ‘rebellion’. On both the occasions I received medals and was even mentioned in dispatches. For my work in South Africa I was given by Lord Hardinge a Kaisar-I-Hind gold medal. When the war broke out in 1914 between England and Germany, I raised a volunteer ambulance cars in London, consisting of the then resident Indians in London, chiefly students. Its work was acknowledge by the authorities to be valuable. Lastly, in India when a special appeal was made at the war Conference in Delhi in 1918 by Lord Chelmsford for recruits, I struggled at the cost of my health to raise a corps in Kheda, and the response was being made when the hostilities ceased and orders were received that no more recruits were wanted. In all these efforts at service, I was actuated by the belief that it was possible by such services to gain a status of full equality in the Empire for my countrymen.

The first shock came in the shape of the Rowlatt Act-a law designed to rob the people of all real freedom. I felt called upon to lead an intensive agitation against it. Then followed the Punjab horrors beginning with the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh and culminating in crawling orders, public flogging and other indescribable humiliations. I discovered too that the plighted word of the Prime Minister to the Mussalmans of India regarding the integrity of Turkey and the holy places of Islam was not likely to be fulfilled. But in spite of the forebodings and the grave warnings of friends, at the Amritsar Congress in 1919, I fought for co-operation and working of the Montagu-Chemlmsford reforms, hoping that the Prime Minister would redeem his promise to the Indian Mussalmans, that the Punjab would be healed, and that the reforms, inadequate and unsatisfactory though they were, marked a new era of hope in the life of India.

But all that hope was shattered. The Khilafat promise was not to be redeemed. The Punjab crime was whitewashed and most culprits went not only unpunished but remained in service, and some continued to draw pensions from the Indian revenue and in some cases were even rewarded. I saw too that not only did the reforms not mark a change of heart, but they were only a method of further raining India of her wealth and of prolonging her servitude.

I came reluctantly to the conclusion that the British connection had made India more helpless than she ever was before, politically and economically. A disarmed India has no power of resistance against any aggressor if she wanted to engage, in an armed conflict with him. So much is this the case that some of our best men consider that India must take generations, before she can achieve Dominion Status. She has become so poor that she has little power of resisting famines. Before the British advent India spun and wove in her millions of cottages, just the supplement she needed for adding to her meager agricultural resources. This cottage industry, so vital for India’s existence, has been ruined by incredibly heartless and inhuman processes as described by English witness. Little do town dwellers how the semi-starved masses of India are slowly sinking to lifelessness. Little do they know that their miserable comfort represents the brokerage they get for their work they do for the foreign exploiter, that the profits and the brokerage are sucked from the masses. Little do realize that the Government established by law in British India is carried on for this exploitation of the masses. No sophistry, no jugglery in figures, can explain away the evidence that the skeletons in many villages present to the naked eye. I have no doubt whatsoever that both England and the town dweller of India will have to answer, if there is a God above, for this crime against humanity, which is perhaps unequalled in history. The law itself in this country has been used to serve the foreign exploiter. My unbiased examination of the Punjab Marital Law cases has led me to believe that at least ninety-five per cent of convictions were wholly bad. My experience of political cases in India leads me to the conclusion, in nine out of every ten, the condemned men were totally innocent. Their crime consisted in the love of their country. In ninety-nine cases out of hundred, justice has been denied to Indians as against Europeans in the courts of India. This is not an exaggerated picture. It is the experience of almost every Indian who has had anything to do with such cases. In my opinion, the administration of the law is thus prostituted, consciously or unconsciously, for the benefit of the exploiter.

The greater misfortune is that the Englishmen and their Indian associates in the administration of the country do not know that they are engaged in the crime I have attempted to describe. I am satisfied that many Englishmen and Indian officials honestly systems devised in the world, and that India is making steady, though, slow progress. They do not know, a subtle but effective system of terrorism and an organized display of force on the one hand, and the deprivation of all powers of retaliation or self-defense on the other, as emasculated the people and induced in them the habit of simulation. This awful habit has added to the ignorance and the self-deception of the administrators. Section 124 A, under which I am happily charged, is perhaps the prince among the political sections of the Indian Penal Code designed to suppress the liberty of the citizen. Affection cannot be manufactured or regulated by law. If one has no affection for a person or system, one should be free to give the fullest expression to his disaffection, so long as he does not contemplate, promote, or incite to violence. But the section under which mere promotion of disaffection is a crime. I have studied some of the cases tried under it; I know that some of the most loved of India’s patriots have been convicted under it. I consider it a privilege, therefore, to be charged under that section. I have endeavored to give in their briefest outline the reasons for my disaffection. I have no personal ill-will against any single administrator; much less can I have any disaffection towards the King’s person. But I hold it to be a virtue to be disaffected towards a Government which in its totality has done more harm to India than any previous system. India is less manly under the British rule than she ever was before. Holding such a belief, I consider it to be a sin to have affection for the system. And it has been a precious privilege for me to be able to write what I have in the various articles tendered in evidence against me.

In fact, I believe that I have rendered a service to India and England by showing in non-co-operation the way out of the unnatural state in which both are living. In my opinion, non-co-operation with evil is as much a duty as is co-operation with good. But in the past, non-co-operation has been deliberately expressed in violence to the evil-doer. I am endeavoring to show to my countrymen that violent non-co-operation only multiples evil, and that as evil can only be sustained by violence, withdrawal of support of evil requires complete abstention from violence. Non-violence implies voluntary submission to the penalty for non-co-operation with evil. I am here, therefore, to invite and submit cheerfully to the highest penalty that can be inflicted upon me for what in law is deliberate crime, and what appears to me to be the highest duty of a citizen. The only course open to you, the Judge and the assessors, is either to resign your posts and thus dissociate yourselves from evil, if you feel that the law you are called upon to administer is an evil, and that in reality I am innocent, or to inflict on me the severest penalty, if you believe that the system and the law you are assisting to administer are good for the people of this country, and that my activity is, therefore, injurious to the common weal.

Share Your Thoughts Now

Do you have interest in reading/listening to the famous speeches in our history? Which is your favorite historical speech?

What did you like about this speech by Mahatma Gandhi? What impact do you think the audience might have felt by the time Mahatma Gandhi was done talking?

Please share your thoughts in the comments section below and add value. Thank you kindly!

I think it is important to set the scene. British imperialism was a balance between principle and opportunism, and it could be moved. The British Government has always understood that it is better to negotiate – provided it does not lose too much face.

As a result of this ‘crime’ Gandhi was sentenced to six years in prison and served two. And as a result of his address, the Rowlatt Act was repealed in 1922.

There are two kinds of opposition to peace and truth. With one kind there can be negotiation and progress.

But with certain kinds of opposition -such as nazism – Gandhi would have been one more victim on the executioner’s block.

God rest his soul.

Hi David,

That’s true. The British imperialism was all about negotiate till it is possible. Push as much as you could and that is how they came as a traders to sell tea and although it took hundreds of years for them to take control, slowly but surely they did get into the ruler’s shoes. India had never seen so cunning and systematic exploiters before.

Anyways, my idea of sharing this text isn’t about what would have happened to Mahatma Gandhi if it was Nazism or any other rule, my objective was to share that very speech, it’s craft and the way Mahatma Gandhi used the forum to get the message out.

The speech is so powerful because it represented his belief system, his faith in non-violence and his consciousness which didn’t allow him to surrender to a mighty force. He stood for truth, peacefully, did what he thought was the right thing to do and said beautifully why he was doing what he was doing.

At the same time, he took the blame for the mishaps because of his movement. Yes, may he rest in peace!

Regards,

Kumar

Ah yes, you asked for other inspiring speeches.

In my teens I learned Mark Anthony’s address on the death of Julius Caesar. I thought Mark Anthony’s rhetoric was so clever – the way it denied everything that it was encouraging.

Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears;

I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him.

Recently I read Sam Leith’s ‘You Talking To Me?’ explaining the structure of rhetoric and its history. I recommend it if you have not read it.

One thing that fascinated me to learn was that the founders of American Independence were schooled in rhetoric and could read Cicero and others in Greek. It is not the picture I had of them at all.

Hi Kumar,

That was a nice write up about the Father of our Nation, as Gandhi is called 🙂

Yes, there is so much to write about this simple and great man that words can often fall short, and it’s wonderful to read about it all on your blog. I guess you were really influenced by his speech. I haven’t had the chance to hear a lot of speeches by great men, but I’ve read about a lot of them, especially when in school and college, and so many of them were part of our history lessons – I still remember them.

Gandhiji and non-violence were things so much talked about in those days – I wish more people would go back in time and see how me really brought it into practice and what all he fought for, all through his life.

How can I forget the Jalliawalla Bagh massacre, that again was something we read in great detail when in school, and have even visited the very place and seen the well. It’s almost like you are living that day, that moment when you are present there, sends shivers down your spine. But it teaches you so much in return too.

Thanks for sharing all of this with us. Have a nice week ahead 🙂

Hi Harleena,

I am not such a huge fan of non-voilence because I believe in the principles of Bhagvad Gita where God himself persuaded Arjun to rise up to the challenge and choose battle to defeat the evil forces.

However, I wanted to share this speech from Mahatma Gandhi because it gives us insights about his thought process and how powerfully he delivered the message. It is about one man who truly believed in what he was doing and who commanded respect from not only his friends but also from his enemies.

This speech is also a masterpiece to learn from for people who are passionate about public speaking. It teaches how to write and deliver a power packed speech that can move your audience to accept your point of view and take action!

Regards,

Kumar

Hi Kumar,

This is one of the greatest speeches ever! When I was a student of the “Foundation of Reconciliation” I learned all about the Jalliawalla Bagh massacre, and all that was going on at that time. Ghandhi’s speech is a great example of how to convey a message with respect and dignity.

I like this particular example because he speaks about his belief in truth and peace and sticks to the point of how he will not surrender.

When making a speech, we have to stay strong to our own convictions, get the message out clearly and ethically.

Thanks for sharing Kumar!

-Donna

Wow! I didn’t know about the “Foundation of Reonciliation”. I am going to check them out a little after I am done replying to your comment Donna! Thank you for sharing about it.

Our own self-confidence and having a clarity of thought is absolutely critical as you said. Mahatma Gandhi demonstrated that throughout his speech through his tone, words and posture. Thank you for stopping by to add value.

Regards,

Kumar

Hi Kumar,

In answer to your question yes I do also study famous speeches. As I think you know I was part of the organization that promoted Robert Kiyosaki and other speakers in Australia and New Zealand. One of the other speakers was Blair Singer who taught a course on powerful presentations. The main feature was students were given one of many famous speeches to deliver. They had to not only recite it but embody it in character. it was very powerful.

This speech was one of them. Of course not in it’s entirety and I cannot remember exactly which part but there is a very condensed version.

Others that students delivered included Marin Luther King (which is my favorite – give me goose bumps every time as it is my dream) and Nelson Mandela.

Clearly Gandhi was an amazing man. Thanks for sharing this Kumar. A topic dear to my heart.

Sue

Hello Gauraw,

First of all thanks for the wonderful post. I guess I’m also on the list of people who really love to listen to read about great speaker and their speeches.

Thanks

Hello Kumar,

Like you, I’m also passionately involved with speeches – especially speeches that emanate from great people who were also very fortunate to have a great heart and head. My best to date however, remains the 2007 Stanford Commencement Speech by Steve Jobs…there’s simply no speech that can uplift a soul better.

Gandhi was great in all respects and without question, he’s one of my favorite leaders. The demeanor he poised through the speech, his confidence, his radical admittance of ‘guilt’ all point to a man who was down to earth – and a man who knew his rights and was prepared to enforce them.

Great share Kumar. Gandhi has left us with a philosophy worth embracing: much can be achieved without arms!

Make the weekend great!

Always,

Terungwa

Gandhi is such a humble person who has been very honest in his living! Thanks for recalling about his life. Articles about such great leaders are always welcomed. Good job author!!

Hy Gauraw,

Gandhi was realy humble and grete person…..you shared realy great information..thanx for this and I really love to listen to read about great speaker and their speeches…great post.

Thank you so much for reprinting this historic speech here – I definitely will be interested in other reproductions of historical significance (which obviously still have profound value today and in the future). Many times people know the historic figures name or photo, but lack a deep understanding of what they stood for and what the significance of their ideas are. Kudos for trying to bring some light and education to this topic.

Best,

Deepak

Hi Kumar,

This really interesting and very good artile. Thanks for sharing please keep on sharing good speeches and articlkes.

if only i could think half as he does. This is so profound, and I am interested in Toast masters too, so i will be looking forward to more interesting historical speeches.

mahatma Gandhi was such a great personality.He play very important role in India’s freedom.You share very interesting information. thanx for this.